Biff's Favorite Books Read in 2023

Come Early Morning

|

| Ashley Judd |

Les Carabiniers

Biff's Best Vintage Films Viewed in 2023

Godland

|

| Elliott Crosset Hove in Godland |

Hlynur Palmason's Godland tells of a Danish minister sent on a mission to a remote part of Iceland in order to establish a parish. The first half of the film details the arduous overland journey that the priest named Lucas (Elliott Crosset Hove) endures and barely survives. Lucas is a nascent photographer who wants to document the sights and people he encounters, but he soon learns that he is unprepared for the harsh conditions he experiences. Furthermore, he is estranged from the natives, particularly his guide Ragnar (Ingvar Eggert Sigurosson) , separated by a language barrier and a vast cultural divide. In the 19th century, the era of the film, Iceland was still under rule by Denmark; it did not gain its independence until 1918. Even when Lucas reaches his destination, he is unmoored and fails to fit in with the community. This leads to tragic consequences.

Palmason is more adept at crafting tableau than in choreographing action. This is not fatal to a film in which man is a speck of dust compared to the vastness and fearsomeness of nature. The film has some of the most spectacular cinematography of recent vintage and it must have been a very challenging shoot for the cast and crew. There are no poor performances, but characterization is somewhat secondary in a yarn that seizes upon mythic archetypes to picture man's dominion as extremely small in the natural order.

Turn Every Page

|

| Robert Caro and Robert Gottlieb |

A film which features arguments about the use of semicolons is going to have a limited audience, but count me very much in that audience. I have eagerly awaited to devour each new volume by Caro pretty much my whole adult life. He combines meticulous research, a broadness of vision, and a literary stylishness that is rare in a historical writer. The boundless affection expressed by the various talking heads in Turn Every Page captures the admiration inspired by his work. That affection is shared by Lizzie Gottlieb, one of the subject's daughter. Normally, I would be hesitant to recommend such a starry eyed valentine to a subject, but I share the reverence and love expressed for these storied collaborators and cannot remain objective about this terrific film.

I Cover the Waterfront

L'Important C'est d'Aimer

|

| Fabio Testi and Romy Schneider |

|

| Schneider and Klaus Kinski |

Birds of Passage

|

| Natalia Reyes |

Jose Acosta plays Rapayet, an impoverished suitor of Zaida who enters the drug trade in order to pay off Zaida's dowry and wed her. He is able to do so, but, eventually, at a dear cost. The film illustrates the next twelve years in the life of Zaida and Rapayet's family and their eventual downfall. Like Guerra's previous film, Embrace of the Serpent, is handsomely shot and also somewhat ponderous. The directors tend to line up their cast in straight lines as if they are a chorus, a technique that is efficient, but unimaginatively static. Still, Birds of Passage resounds as a tragedy of almost Shakespearean dimensions. Mr. Acosta is a blank slate as an actor, but Ms. Reyes, Carmina Martinez as her mother and Greider Meza as her hot headed cousin all create three dimensional characters that add to the desolate feeling of eventual loss.

Mr. Guerra's career has been waylaid by accusations of sexual misconduct. This led not only to a professional split from Ms. Gallego, but also led to the dissolution of their marriage. Because of this, some may be disinclined to watch Birds of Passage, but I would urge all to separate the man from his work and give this ultimately affecting film a gander.

The Best of Ryan O'Neal

|

| 1941-2023 |

I am flippant. That's one of my charms

May December

Todd Haynes' May December, streaming on Netflix, is a bracingly sardonic take on the Mary Kay Letourneau saga. Samy Burch's screenplay differs from the case in ways that make its seamier details a teeny bit more palatable, it was child abuse after all, and helps the film function as an auto-critique. Gracie (Julianne Moore) and Joe's(Charles Melton) relationship does not begin in the classroom, but at a pet store where they are co-workers. This makes the union between the two seem slightly less exploitive, though Joe's status as a victim who was thrust into manhood too early is painfully established by the film's end. The action of the film occurs two decades after the couple's affair became a tabloid sensation. They have raised three kids and have uneasily settled in the town that birthed their affair, Savannah.

An interloper is introduced, Elizabeth (Natalie Portman), a well-known actress who bird-dogs Gracie around town as research for an "indie film" that will be based on Gracie and Joe. Haynes emphasizes the access Elizabeth's celebrity status provides her with tracking and static shots of her gawkers. Everyone in town peripherally related to the duo is eager to spill their guts to Elizabeth. Everything for Elizabeth is grist for the mill. She is a self centered user who shows little regard for anyone, including her fiancée. Her passive aggressive manipulativeness is mirrored by Gracie's, who belittles her children and infantilizes her husband. Haynes seizes upon this by including multiple shots of mirrors and shots from the point of view of a mirror (like above). This proves more effective that the Sirkian use of the same device in Far From Heaven because Hayes and Burch are exploring multiple perspectives instead of monophonically echoing Sirk's critique of 50s conformism. The device here is also a homage the the melding of personalities in Bergman's Persona. The difference being that Elizabeth doesn't bond or meld with Gracie, she just dons Grace's persona as part of her artistic process.

The script seizes between Gracie and Elizabeth's class differences and Haynes and his players are alive to the satiric intent. Gracie is happy to embrace the veneer of the American petit-bourgeoisie. Savannah in the film is a bourgeoise playland with nary a wilted flower or homeless person in sight. Gracie seems desperate to keep herself busy through cooking and flower arranging classes. Elizabeth is an elitist and that can't help but rub against Gracie and her lifestyle. Because of her glamor and psychological astuteness, Elizabeth is able to manipulate Joe into an affair, but to no good end. Haynes uses high angle shots to stress the manipulation going on, most meaningfully during Elizabeth and Joe's act of consummation. Normally, shots of sex stress the intimacy of the act, but that is not the case here. Elizabeth and Grace are succubae draining the life force from Joe. Joe is drained and wallowing in a premature midlife crisis. He is more nurturing than his wife (or Elizabeth). He's good with the kids and, in a metaphor too far, even cares for Monarch butterfly pupae. However, as Elizabeth notes even as she gets in her licks, he is damaged inside and cannot hope to find his way in life.

The last sequence of May December shows Elizabeth performing in the film about Joe and Gracie. The scene displays Gracie brandishing a snake and seducing Joe in the pet shop. The sequence depicts how the media both glamorizes (the pet shop stock room is a veritable love nest compared to one in Savannah) and vulgarizes its subject (that damned serpent). As with the conclusion of Killers of the August Moon, the myths and legends produced by American media are shown to be artificial and somewhat fraudulent. Since The Karen Carpenter Story, Todd Haynes has often used postmodern devices to distance his audience from his subject matter. May December is likewise alienating. Its two leading females are unlikeable and there is no comforting message. This explains popular indifference to the film and also why Charles Melton has won most of the acting plaudits. His character is one of the few sympathetic figures in the film, but I don't think his performance is particularly superior to his co-stars. They are all superb. May December is a knotty, multi-layered film that will reward repeat viewing. It ranks among Mr. Haynes' best films which include Safe, I'm Not There, and Mildred Pierce

First Love

|

| Sakurako Konishi and Masataka Kubota in First Love |

Madeleine Collins

|

| Virginie Efira unravels in Madeleine Collins |

Some have embraced this film as a Hitchcockian thriller, but Barraud is no Hitchcock. Barraud tries to give the film a subjective focus so we can empathize with his protagonist as her world collapses around her, but his directorial personality is not forceful enough to paper over the plot's improbabilities. However, he is fortunate enough in having a leading lady with enough personality and charisma to hold the film's flimsy framework together. Virginie Efira is originally from Belgium where she first found work on television as what they call on the continent a presenter. Her stunning beauty gave her access to film work, but it is her acting chops which has led her to become a significant leading lady in the French cinema during the past decade. She is best known in this country as the lead in Paul Verhoeven's Benedetta. Her sensuality in Madeleine Collins makes it believable that the male leads in the cast are in thrall to her, the most interesting being Nadav Lapid's forger. More importantly, Efira captures her character's hubris which precipitates her fall. Madeleine Collins could have been a film of shattering intensity. That it hold one's attention is mostly due to Ms. Efira efforts.

The Romantic Agony of The Falling

|

| Florence Pugh and Maisie Williams enjoy some splendor in the grass in The Falling |

Abbie (Pugh) and Lydia (Maisie Williams) are best friends, united by their regard for each other and a shared rebelliousness. Their friendship has an almost erotic intensity common to female besties who have not quite ventured into the tumult of heterosexual courtship, like Rosalind and Celia in As You Like It. Things begin to shift when Abbie begins to have sexual experiences with boys, including Lydia's brother, and Lydia feels a little left behind. After her sexual initiation, Abbie begins experiencing fainting spells. Morley explicitly links the ecstatic loss of control experienced during these spells with sexual release. She also links the spells with the occult or, as the pentagram button wearing brother puts it, "sex magick with a k". Abbie dies after one of her fainting spells, a death that has no rational explanation, but that is explained away as "natural". The contagion is not contained, though, and soon the girls of the school are swooning and dropping left and right.

If one is tied down by the dictates of realism, The Falling must seem a muddle. Morley goes to great lengths to avoid any grand psychological reasoning for the fainting spells. What she is concerned with is the pagan pantheism of England's heritage bursting underneath the Christian morality of official culture. The "non-denominational' chapel the school puts on is an empty ritual where students and faculty rotely sing hymns like "All Things Bright and Beautiful." A living culture exists elsewhere. The school seems cut off from the world at large, but the school's grounds are teeming with the natural beauty of falling leaves and swans gliding on the pond. When Pugh recites a Wordsworth poem, "Ode on Intimations on Immortality", a link is made with the Romantics who could spy the preternatural in a puddle.

Morley links this with 1969 by using pop songs of the period and original music from Tracey Thorne, tunes that seem more truly alive than the moldy old bromides sung in chapel. This is apt because the pop stars of that era were truly the descendants of the English Romantics in their rejection of traditional British culture and religion. Donovan, whose "Voyage of the Moon" is sung by both Mary Hopkin and Ms. Pugh in the film, was the nature loving successor to Wordsworth of the flower power era and, like Wordsworth, had a very limited shelf life as a vital artist. Like the Romantics, Morley explores aspects of sex that exist outside the confines of English Christian morality: namely sapphism and incest. Now these themes, particularly Lydia's infatuation with her brother probably doomed the film commercially, but I admire Morley sticking to her guns and exploring aspects of the Romantic tradition that usually get swept under the rug. Certainly, Byron, Coleridge, and Shelley all had a more than passing interest in the theme of incest.

Rationally, I can understand those with issues with The Falling. Pugh, the life force of the picture, is killed off too soon and the film's climax provides little catharsis. However, the film and its concerns stuck with me. The performances of the leads are spot on as are the contributions of Maxine Peak, Anna Burnett, Greta Scaachi, Monica Dolan, and Joe Cole. I group the film with other works by English filmmakers, particularly Ben Wheatley and Mark Jenkin, who are interested in exploring the pagan roots of Perfidious Albion.

The Invisibles

|

| Hiding in plain sight: The Invisibles |

The Orphanage

J.A. Bayona's The Orphanage was roundly praised when it was released in 2007. I found it well-crafted, but dull. Sergio Sanchez's script situates the film in the sick house genre which includes The Fall of the House of Usher, The Shining, and many others. A medium (Geraldine Chaplin) baldly states the film's credo that structures carry traces of past trauma. The protagonist, Laura (Belen Rueda), spent some of her youth at the orphanage and, in a fit of misplaced nostalgia, wants to turn the shuttered building into a home for the disabled. She and her husband are parents to an HIV+ adoptee named Milo who has a penchant for acquiring imaginary friends in a film is overladen with significance, Of course, the ghostly inhabitants of the house start communicating with Milo who disappears, leading to Laura discovering the abode's deadly secrets.

The cast is fine and the visual, sound and production design are so expert that it is not surprising that Hollywood came calling for Mr. Bayona soon after. However, the script is derivative, not only of the above films, but also The Haunting, The Innocents, and the work of The Orphanage's producer, Guillermo del Toro. Also, like The Haunting and The Innocents, two horror classics I'm not crazy nuts about, The Orphanage is overly tasteful and reserved. There is very little sense of palpable horror even when the scarecrow boy attacks and bodies are uncovered. A suitable horror film when one is entertaining an elderly Aunt Sadie and Uncle Mort on Halloween, then.

EO

|

| Jerzy Skolimowski and friend |

|

| Au Hasard Balthazar |

The Round-Up

.jpeg) |

| Janos Gorbe, in black hat, and fellow detainees |

Dark Victory

|

| Death awaits for Bette Davis in Dark Victory |

|

| Davis and George Brent |

For sexual and neurotic appeal, we get Humphrey Bogart as Davis' stable groom. The groom has the hots for the heiress and the insolent banter between Bogart and Davis is fun. Bogart had not yet reached the top rung of stardom. This role was a godsend after playing villainous gangsters for the studio or worse: like his cowboy in The Oklahoma Kid or his vampire in the dire The Return of Doctor X. Another suitor for Davis in the film is played by an actor who never reached the top rung of movie stardom, but overachieved in another field, Ronald Reagan. Reagan plays a drunken playboy. Reportedly, Goulding wanted to give the role a dash of sexual ambivalence, but ambivalence was foreign to Reagan in all aspects of his life. The role must have given him pause because he was the son of an alcoholic, but he acquits himself well.

|

| Davis and Bogart |

Wes Anderson's Roald Dahl adaptations

|

| Ralph Fiennes as Roald Dahl in The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar |

Angst

|

| Erwin Leder and friend in Angst |

Ultimately, Angst has third act problems. Still, it is a tight and elegantly constructed 78 minutes; Kargl's only feature film. Angst didn't generate much goodwill despite Kargl's obvious talent. It was banned in most of Europe and bankrupted the director. Klaus Schulze of Tangerine Dream provides the serviceable techno score though Kargl uses silence and repetitive sounds, like water dripping, to further give a sense of psychic dislocation. The missing link between Stanley Kubrick and Gaspar Noe, Angst will entrance fans of Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer, The Golden Glove, and Sam Raimi. Mom, you should skip this one.

Secret Beyond the Door

|

| Michael Redgrave and Joan Bennett |

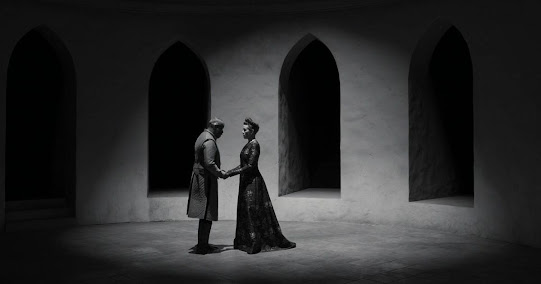

The Tragedy of Macbeth

There are no lousy performances and all the players seem at ease with the text, something you cannot say for many Hollywood version of Shakespeare. I particularly enjoyed Henry Melling, Corey Hawkins, Moses Ingram, Susan Berger, Alex Hassell, and Stephen Root. Kathryn Hunter's performance as the three weird sisters has been justly praised. For those seeking more of this special performer, I would urge them to track down the disc of Julie Taymor's production of A Midsummer's Night Dream from 2014.

Both Denzel Washington and Frances McDormand are fine leads. Macbeth, like Othello, is a warrior more at home planning battle strategy than palace intrigue. Washington is always good at macho swagger and gangster menace, but he is also good at portraying his character's confusion when confronted with forces he does not understand. McDormand has always struck me as flinty rather than fiery, so she is not ideally cast. She does, however, sink her teeth into the text to good effect. I would say she is probably the finest Lady Macbeth yet on screen, but that is damning with faint praise.

Overall, I have my niggles. The finest onscreen versions of Macbeth are Throne of Blood, the second season of Slings and Arrows, and the Orson Welles film from 1948. For a point of comparison I'm going to use the Welles version. It has a subpar Lady Macbeth and raggedy ass production values, but it has a primal spark and pagan passion that the Coen version lacks. Take the scene when Macbeth hires on Banquo's assassins. The killers in the Welles version are skeezy ragamuffins who seem subhuman. I want to take a bath after looking at them. The murderers in the Coen version seem anonymous in comparison.

I also think Coen has bungled the scene of Macbeth spying Banquo's ghost, one of the most powerful scenes in the play. Coen doesn't have Banquo come to the banquet table, but he has Macbeth spy him going down a corridor and then Macbeth pursues him. This ties in with the film's notion of the castle's hallways resembling the haunted corridors of the protagonists' mind, but something is lost. Having the ghost attend the banquet is a symbol of a pagan defilement of the Christian ritual of communion. This is a reflection of Macbeth's devil's bargain with the supernatural and his committing the mortal sin of regicide, a sin very much on the mind of Shakespeare's contemporaries who had just experienced Guy Fawkes attempt to blow up King James I. Ultimately, this is a somewhat bloodless and respectable Macbeth that never captures the pagan furies lurking in the text.

-

Rachel McAdams Sam Raimi's Send Help is genuinely exciting cinema, his best film since Spider-Man 2 . As usual, the pulpiness of Raimi...

-

Matt Clark and David Canary I was surprised by how much I enjoyed Dan Curtis' Melvin Purvis: G-Man , a made for television movie that pr...

-

Takeshi Kitano Takeshi "Beat" Kitano's Broken Rage has languished all 2025 on Amazon Prime with little notice. It is an odd f...

-

Ben Affleck and Matt Damon Joe Carnahan's The Rip is a good meat and potatoes crime film that stars Ben Affleck and Matt Damon and is n...

-

Cillian Murphy I enjoyed the film adaptation of Claire Keegan's novel Small Things Like These more than I expected to, if enjoyment is ...

%20-%20joan%20bennett%20rocking%20a%20part%20down%20middle%20of%20head%202.jpg)